The first successful vaccine was created in 1796, at least known to Western medicine, at a time when inoculation was done by directly infecting a patient with a sample taken from a sick person. These early, fundamental days of vaccination, lab-born vaccines and refrigeration only to be conceived a century later, served as the starting point for what would come full circle in 1960 when a global vaccination effort against smallpox began. It not only changed the scale of vaccination but also the business of transporting and administering vaccines.

A brief history of everything immunisation

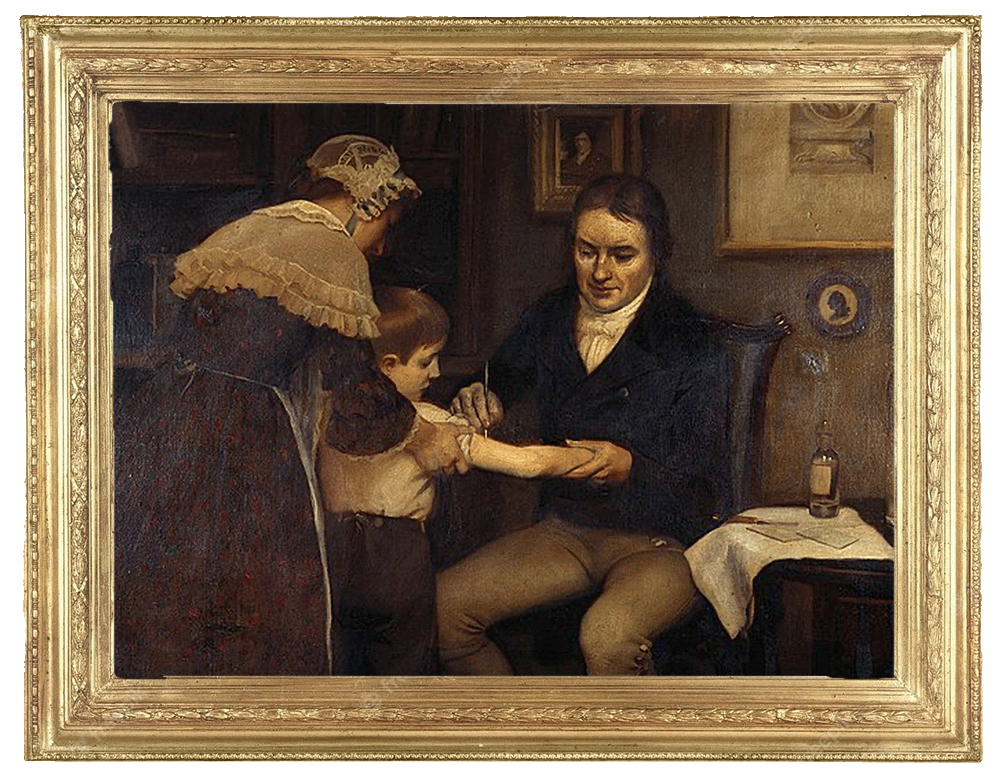

1796 – Dr Edward Jenner created the first successful vaccine when he inoculated 8-year-old James Phipps against smallpox by infecting the boy with a sample collected from a cowpox sore on a milkmaid’s hand. The practice of variolation, wherein a person is infected with trace amounts of smallpox as inoculation, had at the time been practised for hundreds of years in some parts of the world. Jenner’s method of using cowpox to treat smallpox was revolutionary seeing that he was using a less dangerous virus to treat smallpox.

In 1796, Dr Jenner again injected young master Phipps with smallpox two months following his first inoculation. The vaccine obviously working its magic, the boy remained perfectly healthy. Not long after, the word vaccine was coined, deriving from the Latin word for cow.

1800s and onwards – Smallpox vaccination caught on following Dr Jenner’s discovery as governments in Europe and North America mandated vaccination programs en masse.

1940s and onwards – The first mass vaccinations of entire populations happened during the 1950s. The US introduced the DTP vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis in the 1940s, leading to a 99% reduction in cases by 1990. Similarly, the introduction of the polio vaccine in the 1950s led to a rapid decline in polio. By the 1980s, the polio virus had been virtually eliminated.

The latter half of the 20th century saw major advancements in vaccine technology, leading to the creation of new types of vaccines such as weaker versions of viruses (live-attenuated) and inactive vaccines.

It was during this time that vaccination efforts were globalised, thanks mostly to the World Health Organisation (WHO) ramping up its efforts in its vaccination coverage. A key driver of the globalisation of vaccine mandates was, of course, the globalisation of travel and trade which served as a global conveyor belt for disease. SARS, H1N1 and Zika were the obvious culprits that emerged over this time, while the Covid-19 pandemic was, and continues to be, arguably the culmination of these outbreaks. As it would be, the development and administration of such a global vaccination effort also marked a peak for vaccinology.

The Covid-19 vaccine was the first vaccine in history to be developed and rolled out in such a short period, taking researchers between 9 and 12 months to finalise.

How cold chains became cool

Before the luxury of modern-day refrigeration, vaccines were transported much in the same way as other perishable goods, in sealed boxes kept cool with ice packs.

Mass immunisation efforts in the 1950s created the need for huge quantities of vaccines and the transportation of these vaccines to the farthest reaches of the world, which meant the inevitability of vaccines sitting around in containers for long periods of time.

Cold chain systems

Scientist John Loyd explains that the monumental smallpox vaccination effort during the 1960s and 1970s was the beginning of what is today a closely regulated cold chain environment for vaccines. “The need to create a reliable system to keep vaccines cold during the lengthy journey from the manufacturer to the point of use, even in remote areas, was a crucial concern during the early days of the Expanded Programme on Immunization,” he says.

Most vaccines today are stored between 2°C to 8°C for refrigerated vaccines, or below -15°C for frozen vaccines, and are controlled by finely-tuned refrigerators and monitoring systems that keep everything in check. And when things do go wrong, someone will be sure to know about it.

It was a classic case of necessity begets innovation. A lack of methods to monitor heat exposure during transport in this time led to temperature-sensitive monitors that relayed information back to the various parties involved. Further down the line, the storage of vaccines in tropical climates led to modern-day refrigeration designed specifically for vaccine storage and transport. The vaccine cold chain has contributed to one of the world’s public health success stories, says Loyd.

To benefit from our storage solutions, please get in touch with us!